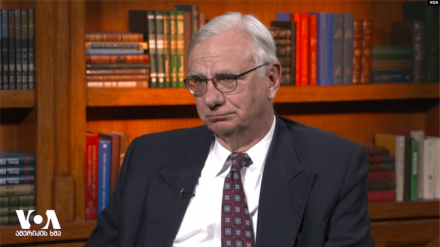

The NATO was founded in April of 1949 by Washington treaty, and at a time aimed to prevent Soviet aggression in Europe. In 21st century, the NATO’s role and agenda has changed. But the Alliance remains a deterrent against growing Russian threat in Europe. Ani Chkhikvadze, reporter for VOA’s Georgian Service, set down with Dr. Hans Binnendjik, Distinguished Fellow at the Atlantic Council, who previously served twice at the National Security Council as senior director for Defense Policy and Arms Control and earlier as an officer for Southern European Affairs. He also served as deputy director and acting director of the State Department’s Policy Planning Staff and as deputy staff director and legislative director of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. He talks about NATO’s mission today, enlargement process, prospects of Georgia’s membership, past successes and future challenges of the Alliance.

VoA: Thank you very much for your time. NATO turned 70 years old. When we look at the history of the alliance can we say that it has accomplished its mission over the 70 years and does it have one today?

Hans Binnendjik: The NATO has been the most successful alliance in the history of the world and it has accomplished its missions primarily to this date. But it’s not mission accomplished. We’re not ready to retire at age 70. If you look back at the history of the alliance of course you have a four decades of the Cold War in which there were 350,000 American troops in Europe, nuclear weapons and a major standoff right across the middle of Europe. As we all know NATO was very successful in helping not only to contain the Soviet Union but eventually to see the Cold War end. Now after that we’ve had another 30 years. And you can break that period down into various decades.

You had a period of the 90s were NATO focused primarily internally on Europe. It was the beginning of NATO’s enlargement and the fights in the Balkans: Kosovo and Bosnia. Then you had the following decade right after 9/11 attacks. And there was a focus on counterterrorism. This was a major shift in the alliance from dealing with major power to dealing with counterterrorist requirements. We saw the alliance making major commitments in Afghanistan helping where it could in Iraq (although there were clear differences over Iraq). And then we have had the fight against ISIS recently. Much of that has been successful. We will see where Afghanistan goes. We’re still negotiating there. ISIS – at least the caliphate – is now pretty much over, its territory is gone. All of that has been successful. The new element in this in the last five years is a resurgent Russia. We see another shift again in the alliance’s mission and requirements to try to deal with new assertive Russia.

VoA: In 90s NATO’s approach to certain extend was to engage Russia. Today we see that NATO is more and more aware of the reemerging Russian threat. How did the policy of the alliance change vis-a-vis Russia and what is the NATO’s Russia policy today?

Hans Binnendjik: Of course the key moment in all of this was 2014. Although it actually began earlier in 2007 with Putin’s speech in Munich and then in 2008, the invasion of Georgia. These were all indicators that things were going wrong. By 2014 we had the annexation of Crimea, the fighting in Donbas, and Putin has done many other things since then. The alliance really began to change, certainly by 2014. And if you look at the summit statements, at the positions of the major nations, there is a great deal of common view about the nature of the Russian threat. Although the intensity of that differs. If you get up into the Baltic states, it’s immediate. If you’re in the southern tier it’s less immediate. But at least in terms of the approach it’s taken and in terms of the official NATO language about Russia – that’s pretty tough.

VoA: When we talk about Russian foreign policy, many believe that the main objective is to see NATO dismantled or divided. Do you think Russians have been able to accomplish that? You discussed how the Russia threat is perceived within the Alliance, and we cannot leave out that we have Hungary and Turkey in NATO. Do you think Russia has managed to divide the alliance from within?

Hans Binnendjik: This is a mixed story. On the one hand the alliance has made a lot of progress in terms of sort of fundamental traditional deterrence of the Russian threat. We have seen in three different summits a series of steps that have been taken: the highly ready Joint Task Force which can deploy quickly, forward deployment of NATO troops in all three of the Baltic states and Poland and at the last summit in Brussels we saw a readiness action plan. All of this taking together really does enhance deterrence along that north-eastern frontline with Russia. That’s the good news. The bad news is that Putin and the Kremlin have been very clever about what we call hybrid warfare, a new generation warfare. They have really been able to exploit differences in societies and use social media to that end. And they have done this very effectively in a number of states. We now have, as you indicated, from your question, a number of states where we have populist rulers, some of whom have increasingly close ties with the Kremlin which is worrisome.

VoA: The North Atlantic treaty was signed in Washington 70 years ago. And as we celebrated the anniversary, we have seen US commitment to the alliance questioned in Washington. The president has previously called NATO obsolete and reports have circulated that U.S. may be considering withdrawal from the alliance, which is very surprising considering the U.S. is the creator of the NATO and keeps it together. Can you imagine the NATO without the United States?

Hans Binnendjik: No, I think the United States is central to the alliance. I mean one could envision a European constellation maybe formed around Germany and France but it would be a very different kind of thing. It wouldn’t be militarily as strong. The United States has almost the external superpower in all of this and has been able to bring along a lot of divergent views in Europe. But, I don’t see that happening. I don’t see a crumbling of NATO.

Just over the last two days we’ve had some strong indicators that that’s true. You’re right that the president during the campaign said NATO is obsolete. He’s come on very hard on burden sharing and rightly so, to some degree, because we have a real burden sharing problem that has to be solved. But just in the last few days we have seen the Secretary General go to a joint session of the Congress. He got almost 20 standing ovations… The House of Representatives recently passed overwhelmingly (almost unanimously minus twenty-two Republican votes) legislation that said the president cannot use appropriated funds to withdraw from NATO. That’s a pretty strong sign. I think there is strong support on the Hill. There is very strong popular support too. 75% percent of the American people think the commitment should remain or become stronger. Nonetheless we do have a president who takes a very strong line on burden sharing that’s having kind of a erosive effect, almost a corrosive effect within the alliance. He’s right on the substance but style is wrong.

VoA: The Administration has been giving a lot more money for European defense initiative. At the same time, these are concerns, as you pointed out, about burden sharing that previous administrations have also raised. Do you think the current rhetoric around the subject is more of a diplomatic play to gain concessions from the Europeans?

Hans Binnendjik: Well you’re right, again if you look at what the United States does – we’re doing a lot and we have changed a lot. We have a third brigade combat team back in Europe, having removed one or two of them in the last administration. We’re strengthening our own presence forward. You mentioned what used to be called European Reassurance Initiative. Now it’s the European Deterrence Initiative and that has gone from say a billion dollars to roughly six billion dollars annually over the last couple of years and that’s been part of the Trump administration, they’ve increased those numbers. Those are all positive signs. There’s been a real focus on 2 percent of GDP for defense and it’s been a useful instrument to try to get Europe to do more. But I think it may be reaching a point where it will be counterproductive. We need to find other measurements for European defense capabilities; not to erase that number or to give them something to hide behind but it is also clear that our European allies are doing a great deal to contribute to mutual defense.

VoA: This has led some of the European allies to start talking about the European defense project including President Macron. This is not a new topic. We’ve seen this happening before and after Saint-Malo. A lot of discussion about European army, and the ability of the Europeans to have a common defense project. Do you think that is something we might see going forward? One could argue that the Trump Administration may be part of the trend and not an exception when it comes to less U.S. engagement in Europe.

Hans Binnendjik: If the United States is going to press Europe to do more and to do a lot more in the way of defense, we can’t be too surprised if they start doing it. The way in which they do it is important. If you talk about strategic autonomy which we’ve been hearing from the French in particular, there’s a certain implication there that it’s exclusive of the United States, exclusive of NATO and that’s not healthy. The same thing is also true for European army if it’s seen as exclusive of NATO. But it doesn’t have to be that way. It is useful that the allies think about operating jointly… This is a healthy thing. That’s the way to maximize efficiencies…

VoA: Let’s move on about NATO’s eastern frontier. In Bucharest, Georgia and Ukraine were promised that they will become members. The Bush administration then was opposed by the French and the Germans on the membership question for Georgia and Ukraine. However, the two countries received a promise that one day, they will become members of the alliance. Eleven years have passed since; Georgia has achieved everything short of membership. Do you think these countries can still hope to become members?

Hans Binnendjik: I don’t think that is going to happen today or tomorrow. But I think you can hold out hope that will happen at some point. The Bucharest pledge that Georgia and Ukraine will someday become part of the alliance has been repeated subsequently. And I don’t think that is done lightly. There are problems in both countries that result in a lack of unanimity within the alliance about earlier membership. Part of the problem is Russian troops on your soil that immediately sort of risks declaring an Article 5. These issues have to be managed and dealt with. But I do see that there is a prospect for Georgia and Ukraine to become members. Meanwhile we have to do more to strengthen both Ukraine and Georgia and that’s happening.

VoA: As you know Germany was divided when it joined NATO; This is something that we see quoted in respect to the occupied territories when Georgia’s membership is discussed. Do you think that’s something that can be used as a precedent?

Hans Binnendjik: Well at that point we had troops right down the middle of Germany on each side. And Germany did come in as a member. So that is an interesting precedent. You certainly don’t want to do anything that cedes Russian troops in Abkhazia and South Ossetia the right to call that sovereign Russian territory. You want to maintain sovereignty but if you can find some formula that’s not a bad precedent.

The debates about enlargement in Washington can be divide in two camps: people who say that the alliance should stop enlarging and people who support pushing the NATO frontlines further. The debates around the membership of the Baltics back in 1990’s were similar. There were people who argued that there was a Russian threat and the alliance would be attacked. Do you think the discussion today around these countries is similar to the debates then?

Well of course it was all new then. I wrote an article back in November of 1991 calling for enlargement of the alliance. I’ve been a strong supporter of enlargement throughout this process and we have gone from 12 to 16 to now 29 and soon to be 30 when North Macedonia becomes a member. You can look at this and ask where does this go now?

There are three clusters of nations who are still aspirants of sorts or where there is a discussion about this. It’s Ukraine and Georgia and those particular cases that we’ve just talked about. You’ve got Finland and Sweden – the neutrals. If they wanted to join NATO, they would be accepted tomorrow. The problem is that their population is so used to neutrality or non-alignment that they’re afraid to have a referendum to support this. And then you’ve got still at least three states left in the Balkans: Bosnia, Kosovo and Serbia who for different reasons are still thinking about how to do that. Enlargement could be a mechanism in the Balkans for bringing more lasting peace. So, this process is not done. But I think it is true that it’s slowing down. It’s adjusting what we’ve got. The Ukraine-Georgia case is perhaps the toughest to deal with because you need it the most. But it’s also the riskiest. Hard to defend.

VoA: The argument one hears often when there is a talk about membership for Georgia and Ukraine is that it will provoke Russia. While others argue that the membership can be a way to deter Russia since Moscow has never attacked a NATO member state. Georgia and Ukraine are in Catch 22 situation where if they are not members, then they cannot have the guarantees and they cannot be defended. But until you get them that guarantee you cannot test the very premise [of NATO’s deterrent].

Hans Binnendjik: On the one hand I would argue that if the Baltic States had not joined NATO in 2004 there probably would be Russian troops on their soil now. That has served as a deterrent. And of course we’ve taken military steps to strengthen that deterrence. That has been a very positive story for the Baltic states. On the other hand, what we saw in 2008 at the Bucharest summit and we know what happened immediately after that. As soon as the alliance said well someday – which was kind of a fallback position – you can become members, Putin immediately attacked and occupied Abkhazia and South Ossetia. There’s evidence on both sides of that argument.

VoA: Do you think that the limited Western response in 2008 emboldened Russia to annex Crimea in 2014?

Hans Binnendjik: It’s hard to say what the cause and effect was. But I would say that the policies that followed after what happened in Georgia were relatively weak. The United States was preoccupied in two major trillion dollar wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. We may have just taken our eye off the ball and the Europeans were really not interested at that point in dramatically expanding their commitments.

VoA: And lastly the European countries have traditionally been more reluctant to allow more member in the alliance. We saw North Macedonia succeed but we don’t know if that will curtail the appetite for enlargement or reaffirm the open door policy. We can argue on both sides. Do you think for Georgia the relationship with the United States and the security guarantees that Tbilisi can get from Washington in the end of the day maybe a more realistic path?

Hans Binnendjik: In the long run, I think Georgia can still hope to be a member of the alliance. I wouldn’t give that up and I would hold the alliance to those pledges. But in the meantime you have to take other steps. We have the NATO-Georgia Council which is useful, there are NATO training programs in Georgia, there is a lot of bilateral assistance and joint exercises that are done. This is a way I think – through practical political/military means to try to strengthen these ties as much as possible. And to also let Russia know that they have a hell of a fight on their hands if they try to take more Georgian territory.

By Ani Chkhikvadze, Voice of America’s Georgian Service