TBILISI, DFWatch–When I heard Paul Manning, an anthropologist from Trent University (Canada) is visiting Tbilisi, I knew I had to meet him. Not only because of his papers on toasts and supra culture, cartoons during the Rose Revolution, notion of terror in Pankisi, or his newest book on sexual traditions in Pshavi and Khevsureti. I was also interested in his memories from early days of independent Georgia.

A fluent Georgian speaker, Manning arrived to Tbilisi in 1992, when the country was taking its first independent steps away from the Soviet Union.

“When the Soviet Union officially fell apart,” Manning starts, “the Government of Georgia had no embassy. So there was no one to grant a visa. As there was no way to get Georgian visa, I had to get Russian visa instead.” To do that, Manning (then a graduate student in the University of Chicago) forged an invitation letter from the Tbilisi State University (TSU) using ‘bad English’ and faxing it back and forth between the U.S. and Russia, because to wait for a real invitation letter would have taken too long: “The forged letter was a masterpiece. In that time, Georgians under no conditions would use Russian. I didn’t have to forge Russian or Georgian letter, I could forge an English language letter. And so the letter was in bad English, which turned out to be the key to its success.”

Georgia in 1992 was not an easy place to be, Manning continues. As he had invited himself, TSU had no idea what to do with him and wanted $5000 for enrolling to Georgian language classes. He managed to delay his payments and to sneak into auditorium through the back for a while. But he still needed to get registered in Georgia. But through his host family’s connections, he managed to work things out: “They had relatives in the Academy of Science. We went there once together, and the second time I went there by myself. The second time, still no one was willing to help, but there was a guy using their phone to make long distance calls. He overheard my problems, took me to a khinkali restaurant, and later to his friend, who worked at the registration place. He got me in the front of huge lines and got all my stuff processed. This guy saved my life.”

Apart from corruption and necessity of personal connections, everything else was fine, says the anthropologist, even if everyone had guns and streets looked unsafe. “There were two types of people with guns and some sort of a uniform. There were Tengiz Kitovani’s National Guard of Georgia, and Jaba Ioseliani’s informal militia, Mkhedrioni. The latter wore sunglasses. That’s how you tell them apart. And apart them, there were people with guns and no uniforms,” he remembers, and adds that it seemed more dangerous than it actually was. “People wanted to have guns to show that they were strong and independent. But they didn’t shoot as many people as you might think. I never saw a corpse in Tbilisi.”

When Manning first arrived, Tbilisi still had electricity, but it was already disappearing. Hot water also became scarce, and in the end of 1992 was available only on weekends.

His $4000 stipend lasted about 11 months. “It would had been nice to stay longer in Georgia, but Georgia was difficult at that time, harder than Moscow. When I came back to the U.S., I never wanted to go back,” he says.

However, towards the late 1990s, Manning started thinking about Georgia again. He got in touch with his friends, applied for grants, got three year funding and returned to Georgia in 2001. This time he stayed until 2003.

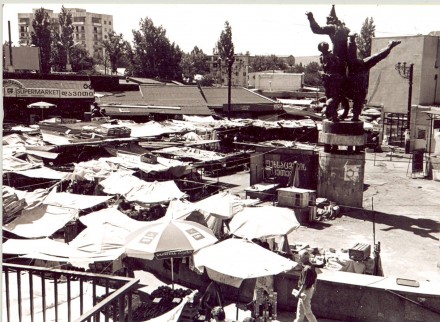

When he came back, he was shocked by the look of Tbilisi. “It was shabby. They had eliminated all the socialist art by that time. It was replaced by things you see now in the streets, but all was sleazier and crappier. It was 1990s, it was the sleazy transition. Also, if you knew anyone who had a lot of money, you knew they were doing something unpleasant. When you saw expats from Georgia in other countries, you didn’t talk to them. It was like, ‘oh. what are you doing here? How did you get here? Who did you kill?’ Or something similar,” contines Manning.

But Tbilisi at least seemed safer, as there were no guns. “Shevardnadze does not get a lot of credit, but he disarmed Georgia. My theory is that he broke the back of Ioseliani’s Mkhedrioni and Kitovani’s National Guard by the Abkhaz war. All these disorganized Georgian rebels, Jaba’s Mkhedrioni, were just terrible. They were thieves, they robbed people and Georgia. The National Guard was no better. And the worst thing that can happen to an armed organization of thieves, that calls itself an army, is an actual war. Because then they actually have to go and fight,” Manning continues. “ There’s no way that any reformers later could have done anything, if he hadn’t done that. If there still is a heavily armed crazy militia, then there is no way you can do anything.”

Arguably, the most intriguing part in the early 2000s was Misha Saakashvili’s road to power and the Rose Revolution. “I missed the revolution itself, because I was back in Canada teaching, But I saw it coming since 2001, when there was a protest about Rustavi 2, which was an important thing,” Manning recalls.

He continues telling how just after the revolution all country was in love with Saakashvili. “Everyone loved Misha. You couldn’t say anything bad. But I was more sceptical. All people wanted, was a messiah. They weren’t really paying attention to what he was doing, and some things were really dodgy, like strengthening the military and special operations in Pankisi, repression in periphery. Plus, he kept telling that Americans will join Georgia toe to toe against Russians, so when 2008 happened, people were surprised. But Americans joining would have meant WWIII, and it is not going to happen over Ossetia,” Manning says.

He finishes our conversation with a parallel between Ukrainians and Georgians. “Ukrainians are like Georgians twenty years ago and ten years ago combined. There is the desire to repeat all the mistakes that the Caucasus made. From both sides. It always takes both sides, Georgians and Abkhazians, Georgians and Ossetians or Ukrainians and Dombassians. There is no point to pick which one is worse, they all are. The worst thing is that ordinary people are suffering,” he says, “Ukraine now is like Georgia in 1991-1992, and both sides act like Zviadists. Also, they act like Rose revolutionaries in 2003 and they love Misha, as he is the last gasp of the Color revolutions.”