President George H.W. Bush will be missed not only as a historical leader but also for the style of leadership he brought to Washington: calculated, diligent, often bipartisan, driven by conviction, guided by humility, and resolute. Georgia owes him a great debt.

President George H.W. Bush will be missed not only as a historical leader but also for the style of leadership he brought to Washington: calculated, diligent, often bipartisan, driven by conviction, guided by humility, and resolute. Georgia owes him a great debt.

President Ronald Reagan is often credited with signaling the beginning of the end for the Cold War, ending Europe’s East-West division, and perhaps triggering the process that would lead to the dissolution of the USSR and, consequently, Georgia’s independence. His Brandenburg Gate “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall” speech marked my generation, allowing us to hope that decolonization and independence could be achieved in our lifetime. But it was President George H.W. Bush that managed that project, shoulder to shoulder with Eduard Shevardnadze, Helmut Kohl, Margaret Thatcher, François Mitterrand, John Major, Hans-Dietrich Genscher, Douglas Hurd, Roland Dumas. Bush belonged to a cohort of leaders for whom Europe’s unity was a lifetime achievement, too precious to be taken for granted.

The magnitude of their feat is hard to overstate. The issue at hand was not merely to appease Russia, where hardliners were infuriated by liberalization at home and overtures to the West abroad. Part of the problem was Europe itself, where leaders feared the prospect of a reunified Germany, whose unity was an open question. To this pulsating, complex, frequently controversial discourse among world leaders, Bush Senior brought the resilience of an oilman and the foresight of a CIA man; but he left his Texas guns at home.

President George H.W. Bush was a shrewd political project manager, who made a difference by meaningful silence and hard work. In Nov. 9, 1989, East and West Berliners took sledgehammers to the Berlin Wall; President Bush did not boast of US might and did not dwell on political triumphalism, which may have cost him his reelection. Bush did not undermine President Gorbachev’s calls for a “common European home” and took the time to reassure President Francois Mitterrand that Washington, through NATO, would be ever-present in Europe not only to offer security but also as an external rebalancing actor.

While analysts of all kinds trumpeted the inevitable victory of democracy and peace, President Bush surrounded himself with strong personalities rather than slavish “yes men.” As noted by Richard Haas, President Bush assembled what was arguably the best national security team the U.S. has ever had: Brent Scowcroft, Colin Powell, Dick Cheney, Robert Gates, Larry Eagleburger, William Webster, and others.

Meaningful silence was President George H.W. Bush’s strong hand. His communications were sometimes debatable to outsiders. Most Georgians still remember the August 1991 message President Bush delivered in Ukraine, which the New York Times labelled the “Chicken Kiev” speech. At the time he called on nations craving for independence to leave behind their national aspirations in favor of a Union Treaty. In doing so, he echoed Margaret Thatcher who told the Boston Globe that she would no more open an embassy in Kiev than she would in San Francisco. In Georgia, I recall, President Zviad Gamsakhurdia, of whom President Bush once admitted that he was going against the tide in the global affairs, did not take kindly to that “Chicken Kiev” speech. Indeed, our first national leader could not see that Georgia was only one among many of Washington’s considerations.

A few years ago, a former Georgian MP recovered a draft letter by President Zviad Gamshurdia, addressed to Bush’s Secretary of State, James Baker and delivered that to me. Going through references to Thomas Jefferson and George Washington, Georgia’s first President demands international recognition, here and now. The letter itself never reached its destination and was nearly burned by KGB operatives that had infiltrated the President Gamsakhurdia’s office. But what is clear was that our first President argued in the name of faith, principles, right and wrong, rather than envisioning a new world order in which Georgia would find its place, as a prophet of national independence. President George H.W. Bush was more down to earth.

Although he was the first US President with the weight of “planetary leadership,” his priority was managing the transition to what we later called an “international community.” And from that point of view, the priority was to ensure that the disintegration of the USSR would not result the dissemination of weapons of mass destruction. The challenge thrown upon President Bush was to ensure that a 50-year “balance of terror” did not turn into a perfect storm of terrorizing imbalance. He new that there was nothing inevitable about world peace. Peace was a fragile project, filled with dirty, rough work, and President Bush was determined to shape rather than react to the unfolding historical narrative.

We will miss President Bush’s sense of historical responsibility, which took him from the wreck of a WWII bomber to the White House. And it is perhaps this sense of history that made him a close friend to Eduard Shevardnadze. Bush’s Secretary of State, James Baker, and the last foreign minister of the USSR, Eduard Shevarnadze, submitted a common resolution for the immediate and unconditional retreat of Iraq from Kuwait in 1992. Together, they envisioned a new international community, in which the United States would lead its allies, with a clear sense of purpose and direction, taming war to serve peace.

Like President Bush, President Shevardnadze knew that there is no such a thing as a historically inevitable development. Reborn as a Georgian statesman, President Shevardnadze knew that Georgian independence was just a burning desire that could fade away. At their first meeting at the Helsinki OSCE Summit in 1992, Eduard Shevardnadze, as Head of the State Council, turned to President Bush for urgent humanitarian assistance. The US President obliged. In fact, President Shevardnadze frequently admitted to his foreign interlocutors frequently “Georgia survived as an independent and sovereign state because President Bush acted decisively.” It all started when President Bush dispatched Richard Armitage to arrange the delivery of the first shipment of grain, saving thousands of Georgian families from starvation. Over the years, more aid would follow: in food, hard cash, know-how, military equipment, training, scholarships, and goodwill, for which the citizens of Georgia will be always grateful. Politically, the start is always harder, because you need to make the case that a small country in the South Caucasus is worth the trouble. President Bush made the case in Washington that transforming the post-Soviet space required the balance of help with reform, a recipe that in later years both the United States and Europe would rebrand as “conditionality.” But, this was clearly a transformational agenda, driven by values, not narrowly and myopically transactional.

To this day, I recall Eduard Shevardnadze introducing me to Rich Armitage as his “National Insecurity Advisor,” against the sound of Kalashnikovs in the streets of Tbilisi, as civil strife ravaged Georgia. While Richard conveyed the warmest regards of President Bush, we were interrupted by shooting, leading our American friend to comment ironically that perhaps Shevardnadze had more friends in Washington than in Tbilisi. And American friends dispatched by the Bush’s Administration kept landing in Tbilisi.

As Secretary James Baker arrived in Tbilisi in 1992, the Bush White House was making clear that Georgia was a country with a powerful friend, ending its diplomatic isolation. Secretary Baker arrived with Gen. John Shalikashvili, the Bush Administration’s candidate for Supreme Allied Commander in Europe. General Shalikashvili, whose father fled the Bolsheviks in Georgia in 1921, was the United States Army commander for allied relief operations in the Persian Gulf War. And Shali was also a messenger of hope to Georgians, conveying with his name the prospect of a different relationship with the West, one in which our independence was relevant and indeed desirable by our American friends.

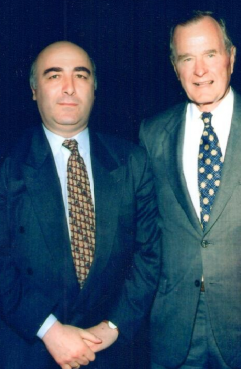

During my Ambassadorial term in Washington I had a privilege to meet the President Bush and his lifetime companion, Barbara, at their Houston residence. That was a meeting arranged by Constantine S. Nicandros, Chairman of Conoco Inc, and a close family friend. After I introduced the Chairman of the Georgian parliament, Zurab Zhvania, to the President and Mrs. Bush, the conversation drifted to the last days of the USSR. We then talked long about Georgia and its future and felt at home, interrupted only by a lovely poodle, excited to see new faces. “You see how everybody in this family admires Georgians!” Bush Senior casually said with a warm smile on his face, making us feel truly at home.

Years later, during our meeting in the Oval Office President George W. Bush told President Shevardnadze the he had received an early morning phone call by his father from Houston: “Wake up and get ready, you’ll be meeting a member of our family and behave!” was the message the US President cheerfully reported to the Georgian delegation, making everyone feel welcome, and comfortable. Relations between Georgians and Americans always had a personal dimension, but I have never quite understood if that was because Georgians are Georgians or the Bush family is the Bush family.

What is clear is that every Georgian owes a personal debt to the Texan whose home – wife, sons, and even the dog – were always welcoming, embracing, and supportive. And not only the Bush family members but all the President’s people – Secretary Baker, General Scowcroft, Secretary Rumsfeld, General Powell, General John Malkhaz Shalikashvili, Condoleezza Rice, Rich Armitage, Bob Zoellick, Dennis Ross, John Kornblum, Dan Fried, Paul Goble and many others – stood by Georgia, nourishing the relationship whose first seeds were sown by George H.W. Bush himself.

As you go from the Shota Rustaveli International Airport to the Tbilisi downtown, you take a road named after a Bush. We made this family part of our own home.