Mestia, DFWatch – Svan language activists explain why it’s necessary to stop the decline of the language amidst reluctance on behalf of the authorities and the Church.

‘A language is a dialect with an army and navy’, said famously Jewish sociolinguist Max Weinreich, referring to the impossibility of formal distinction between a language and a dialect, at the same time hinting at the political aspect of the debate.

With words like kut (‘khachapuri’), läyr (‘book’), or laqwra (‘window’), eighteen vowels, and three extra consonants, Svan is incomprehensible to Georgian speakers — many of which still insist that Svan is merely a dialect of Georgian.

Svan is spoken by some 23 thousand people in Svaneti (Shwän), which consists of municipalities of Mestia and Lentekhi (Lentekha). Svan also used to be spoken in the Kodori valley (Däl) in Gulripshi region of Abkhazia until 2008, when local pro-Tbilisi government was pushed out by Abkhaz and Russian forces. There are pockets of Svan speakers in Kvemo Kartli and Kakheti due to resettlements in the Soviet period. Finally, there are Svan-speaking communities in Tbilisi, Moscow, and some EU countries, especially Greece and Italy.

Together with Georgian, Laz, and Mingrelian, Svan belongs to the South Caucasian language family. Throughout the history, Georgian served as the language of literature, administration, and prayer for speakers of these languages.

Changing environment

The decline of the Svan language is a fact. The online edition of Ethnologue: Languages of the World classifies Svan’s status as shifting, which means that ‘the child-bearing generation can use the language among themselves, but it is not being transmitted to children’.

Giorgi Chartolani, better known as Father Giorgi, a priest in Mestia and a Svan language activist corroborates the claim.

‘I conducted a monitoring project, during which I visited schools in all the villages of Mestia municipality. 50% of children couldn’t speak Svan at all, 40% could speak it at a basic level, and 10% could partially speak it. Even I can’t speak Svan fluently, like my grandfather did. It is a common phenomenon now that people use Svan vocabulary to try to convey a meaning which is directly translated from Georgian.’

Father Giorgi connects the shift in language practice with the advance of modernity to Svaneti:

‘The generation of people in their forties and fifties still use Svan as their spoken language, although there are very few occasions on which they can speak it. It is a part of the process which can’t be stopped. I was fourteen when TV was first introduced to Svaneti. We had radio, but there was neither internet nor mobile phones. Before the technological advance, we spoke Svan in families and with other villagers. Nowadays, it has become more difficult. Svaneti has become more integrated with the rest of the country by means of migrations and tourism. It’s not a negative process per se, but it disrupted the Svan-speaking environment. If a person speaks Georgian at work or at school, after which they come home to watch TV and browse internet in Georgian, they become more exposed to Georgian than to Svan, at the same time having less time to communicate with their families in Svan, which hinders the natural development of the language.’

‘In my childhood, whenever we had a wedding, wake, wooshtkhweshd (‘wake held 40 days after death’), or linzaurääl (‘commemoration of the dead after one year’), Svan was the only language used throughout the ceremony. Today, it is common to have guests who don’t speak Svan, so the whole ceremony is held in Georgian. There is no time and space left to speak, develop, or even preserve Svan.’

Local efforts

A handful of local activists have attempted to reverse the worrying trend of decline of Svan.

Richard Bærug, partner of Grand Hotel Ushba in Svaneti, has coordinated and participated in a variety of events aimed at preserving Svan.

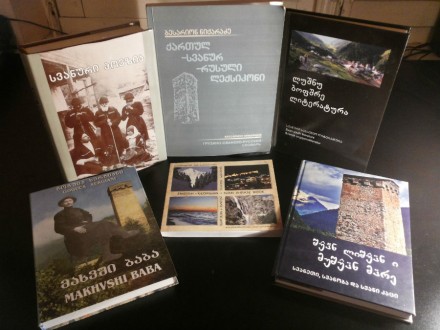

‘For the second time we have now organised a Svan literature competition for children and youth between 12 and 18 years old in order to raise the prestige and popularity of the Svan language among young people in Upper and Lower Svaneti’, Mr Bærug tells DF Watch. ‘The second book will be published in December with a compilation of 12 stories written by young authors from Lakhamula (Lakhmyl), Chokhuldi (Chokhuld), Tvebishi (Twebish), Mestia, Tsvirmi (Tswirmi), Ushguli (Ushgul) and Lentekhi (Lentekha).’

‘My friends and I have tried to use the Svan language in everyday life as any other modern European language. For instance, our hotel information and signs are in Georgian, Svan, and English; our hotel website is in many languages, also partly in Svan. The Svan language is used in new hiking signs in the mountains. In our sport competition we usually have all information in Georgian, Svan, and English. We were involved in organising a library project where for instance the introductory seminar offered translations into Georgian, Svan, and English. Last, but not least, in May there were Norwegian film days in Svaneti where the program was in Georgian and Svan and the subtitles of the movies were for the first time in history in Svan.’

One inhabitant of Mestia told DF Watch that they were harassed by local Church representatives, who threatened to take the issue to court, for their involvement in the Norwegian film days. Although Mr Bærug describes local community’s reaction to the activities as overwhelmingly positive, he admits that there has been some institutional resistance.

‘People are happy that more serious attention is being given to the local language. However, some years ago, when we did the library project, we experienced some repression. We were kicked out of promised premises for the kick-off seminar in Mestia since the working language was Svan in addition to Georgian and English. Local librarians were threatened that they would lose their jobs if they took part in a seminar where the working language was Svan in addition to Georgian and English. The local authorities also wanted to censor the Svan version of the project’s website. But with the change of the government, the attitude towards the regional and minority languages has fortunately changed for the better, in a more modern European way. Now, for instance, the local government in Mestia, alongside foreign embassies and other entities, is among the supporters of the Svan youth literature competition.’

Political issues

The phantom of Abkhazia and South Ossetia–like separatism has affected the debate on minority languages in Georgia. Many fear that recognising Svan as a separate language might have political consequences.

If Svan isn’t recognised as a language, it won’t be eligible for protection under the still unratified European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.

In September, the Ministry of Reconciliation and Civil Equality stressed the importance of ratification of the charter — a commitment assumed by Georgia upon acceding to the Council of Europe. While dialects are ineligible for protection, it remains unclear which languages will be defined as such.

DF Watch asked Father Giorgi for his opinion on the issue.

‘Svan is quite peculiarly considered a non-literary language, as the majority considers it a dialect rather than a language. In such a view, dialects don’t deserve to be used for creating literature. This is a politicised approach.’

‘We don’t hold grudge against the state and the national unity, but within this unity there is a question of minority languages. Why should minority languages be punished for the fact that they are spoken by minority communities? Why should they be annihilated? It’s hurtful that Svan is considered a security issue’, Father Giorgi says.

Father Giorgi admits that there is a political undertone in the debate on the future of the Svan language.

‘I was told that this type of activism may “look like separatism”. Separatism is not in our nature. How should some 30 thousand people separate themselves anyway? Separation doesn’t lie in our ambitions, but saving our language does.

‘In times when Georgia was united with Russia, whether within the Russian Empire or the Soviet Union, Georgian was discriminated against. It was called “a language of dogs”. It wasn’t pleasant. We have an analogical situation with Svan today. It doesn’t matter how many we are. Don’t disturb me in my efforts of saving my language. On the contrary — help me to achieve that. This is a question of respecting my rights.’

The Georgian Orthodox Church has actively promoted a Georgian identity which is supported on pillars of religious and linguistic unity. Father Giorgi admits that in case of his language activism, the Church has demonstrated an ambiguous approach.

‘During my visits in Svan villages, someone apparently didn’t like what I was saying about the situation of the Svan language and thought it bore signs of separatism. This person reported my behaviour to the archbishop. The Patriarchate asked me to come to Tbilisi to make explanations, after which they decided to move me from Mestia to a different location. After local community protested against their decision, the Patriarch agreed to let me continue my service in Mestia. I don’t really know the behind-the-scenes of this incident.

‘The entire Georgian Christian literature was written in Georgian; there are no known written relics of Svan. The Georgian language symbolises the unity of the Georgian Orthodox Church. On the other hand, European countries used to have Latin as their language of liturgy, but now each country uses their own language. It demonstrates that having different liturgical languages doesn’t necessarily undermine the unity of the Church and its doctrine.’

Future of the language

While the issue of the preservation of the Svan language is seldom raised and the problems are mounting, Mr Bærug shares his ideas on how to secure the language’s future.

‘I believe it is important to change the increasing trend that parents do not speak Svan with their children as they fear that speaking it may harm their children at school. In such a way this unique Kartvelian language could die out quite soon. I think Georgia maybe should look to Switzerland and see what measure they take to support the small Romansh language. As a start it would be very good if the Ministry of Education made a decision to gradually introduce Svan as a subject in the schools in Svaneti, the starting goal possibly being two or three weekly lessons of Svan. In a longer perspective, the Georgian authorities could look at the best practice experience of bilingual education in the first grades in other European countries.

‘Technically it would be good if the Ministry of Education in cooperation with the private sector took measures to make it possible to write Svan correctly on the internet and mobile devices, that is with all the letters characteristic for the Svan language.

‘As the Svan language is a unique part of the Georgian and European culture heritage, being possibly one of the world’s oldest languages among those that are still being used and which, in the course of time, have changed little, I believe it would be very good if the Ministry of Culture together with the Ministry of Education developed a program to raise the prestige of the Svan language, that is allocated financial support for the endangered Svan language on the state budget with available funding for producing books, online and paper publications, maybe also radio and TV programs in this ancient Kartvelian language.

‘I have heard that plans are under way for the Georgian government to possibly grant the Svan language a status as a regional/minority language. I think this would be very welcomed, not only by the EU, but most of all by all those people in Georgia understanding the currently very difficult situation for the small and unprotected Svan language.’

Father Giorgi also indicates the state as an actor that has resources and legitimacy to reserve the worrying trends.

‘Only the state can help the Svan language and support its development as a part of Georgia’s cultural heritage. Its preservation isn’t in the interest of business circles such as media companies, because the community of Svan speakers is too small to generate profit. The state should step in and support Svan.’