TBILISI, DFWatch–Things did not change for the better when Davit Vanishvili’s house ended up on the other side of the border with Georgia’s breakaway region South Ossetia several years ago.

DFWatch recently visited some of the villages on the administrative boundary line (ABL), and we had a chance to speak with Vanishvili through barbed wire that runs through his garden, installed by Russian border guards.

He does not receive pension from de facto government and has to withdraw his pension from Georgian-controlled territory. To do this, he has to sneak over to the other side of the ABL.

“Once I was detained and taken to Tskhinvali. I went to get my pension. On the way back, I was caught. I went to Khurvaleti [a village on Georgian-controlled territory next to the ABL]. They were hiding, waiting for me,” he recalls.

Vanishvili claims Russian soldiers often spy on him around the time when pensions are paid.

“I have to sneak out at night. Sometimes I stay overnight with relatives or neighbors. How else can I survive? They don’t give me anything and I cannot even buy salt for Georgian laris. Where on earth can I get Russian money?”

Three years ago, he continues, some people came to his house and took his Georgian passport and driver’s license and other documents, promising to make a new passport, but they never did. Now he has no documents.

Neighbors from the other side of the barbed wire fence usually help him out with food and other needs. The Russians guarding the perimeter often reprimand him for this.

“Do not talk with the neighbor, they say. I want bread, am I not pitiful? What will happen to me? How long should I go on like this?” he asks, adding that the Russians offer him to leave if he doesn’t like it there, but he says he cannot abandon his house as he is sure it will be destroyed in a week.

We were guided into the villages by Georgian servicemen, who made sure that we weren’t detained for ‘violating the border’, which happens often in these villages.

One of them, who took us to meet Davit, told us that often when Davit speaks to journalists or other guests, he is often interrogated afterward.

We spoke with Eldar Dvalidze and Zurab Tukhiashvili in the village Kodistskaro. Their main concern is irrigation water. While we were on our way to the village, we met the two of them as they were working in the field on a cold snowy day, processing the soil with a tractor with the help of their ethnic Ossetian friend.

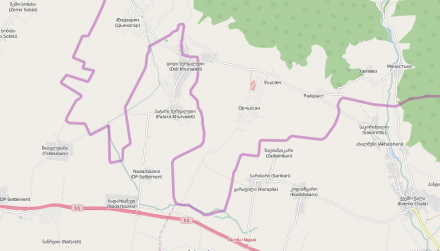

They explained that there are lots of Ossetian families nearby, like seven households in the neighboring village Saribari, 15 in Zariantkari and about 20 in Karapila, and they have good friendly relations.

“I can head right to their family right now and go inside without asking and we communicate in Georgian,” Zurab said.

They explain that it is easy for the people from the other side of the ABL to cross over to Georgian-controlled territory, but they can’t do that themselves because they will be instantly detained and taken to Tskhinvali, and only released after paying 2,000 rubles (USD 25).

“There aren’t so many detentions in our village. But [Russian border forces] are searching in other villages for people who are working in the field,” Eldar says.

Detentions happen even if a person hasn’t technically crossed the border.

“If they catch you, they take you and you can shout that you haven’t crossed anything, all in vain.”

Both recall the time before the 2008 war, when the relation were warm and friendly.

“Imagine, there was a marshutka from Tbilisi and Gori to Orchoshani (a village, which is not Georgia controlled anymore). We had [means of] transport. If we wanted wood, we went there, or they would bring it here. They were also dependent on Tbilisi and Gori, for example if they wanted cattle. People’s diplomacy was winning. But Russia didn’t like it and did what it usually does,” Eldar says, referring to the conflicts in Azerbaijan and Armenia, in Ukraine and Moldova.

“70 percent of our daughters-in-law are Ossetians. Ossetian women raise Georgian children, but it didn’t suit Russia that we were too warm with each other.”

Locals in this village usually harvest wheat and barley.

“We keep staring at the sky. If it rains, we are lucky, but if not, we are left with nothing.”

During the months and years after war in August, 2008, Russian border guards have kept moving the border, installing barbed wire and fences, and putting up warning signs. In a deserted area near Gori, the border runs only 400 meters from the main E60 motorway, a road of international importance.

Right next to the motorway, on roads leading to villages, there are Georgian checkpoints beyond which it is not possible to go without permission. The guards are careful to prevent people from getting detained, and check everyone passing through the roads.

The border is not marked everywhere. In Saribari, for example, villagers know approximately where it is and tried to explain it to us by reference to a small pit on a hill.

We met with Ossetians living in Tsitelubani. Middle-aged and elderly men were gathered discussing local problems. They explained that in the village there live Ossetians, people resettled from Adjara, in the southwest of Georgia, Meskhetian Turks and others, all living in peace.

According to Vasily, people’s biggest concern in this village is lost agricultural lands. Last year was the last time they were allowed to harvest their lands. They are now on the other side of the ABL and they cannot do anything about it.

“150 meters left is the border. Over there, there is the border as well. We are in the middle. We don’t even have a space to keep a calf. There is no pasture,” he explains.

It doesn’t matter whether it is Georgian or Ossetian or other. All are detained at the ABL and only released after paying 2,000 rubles. One of the people we met told us that he has two sisters in Tskhinvali, but cannot visit them. They only talk by phone.

Those who still have Georgian passports come here to receive pensions, and then return.

“I also want to go there, see my nieces and nephews, but how? No-one will let us,” he says. “You are detained even out with the herd.”

Villagers in Tsitelubani speak of the possibility that there may be issued some kind of permission for them to visit relatives for a day or two.

“What would happen? They discussed it in the past, but then they forgot this issue. It would be nice if the government or anyone carried out this initiative.”

Irrigation water is also an important problem in Tsitelubani. People cannot even remember last time they had water. They have 10-12 meter deep wells for water, but it is enough to drink, not for irrigation.

“Can you see a tree here? You couldn’t sees the village from the highway in those times. It was covered in green. We threw away the fruit and fed our animals with it. Now we pay 2 laris for a kilo of apples. A man from Tsitelubani buying apples for a fortune, ridiculous.”

Salim Iskanderov, a Meskhetian who was repatriated to Tsitelubani, tried to explain us the situation in on sentence.

“It’s not even an occupation. Here lies Georgian army. There lies Russian army. We are in the middle. There is no ‘patron’ [someone who takes care of us]. We are abandoned. Any person living here would say the same.”