Most girls in Duzagrama get married and drop out of school before ninth grade. (DF Watch.)

TBILISI, DFWatch–Pariz Alakhverdiani, 17, is in 12th grade at the public school in Duzagrama, a small village in southeast Georgia populated by ethnic Azerbaijanis.

Alakhverdiani wants to study at the Medical University in Tbilisi and has decided to become a dentist. To be accepted, he has to pass five exams at school and then two national exams.

He is taking additional lessons to prepare for the exams.

“I want to come back here when I am finished with my studies. I will stay in Tbilisi to work,” he tells DF Watch.

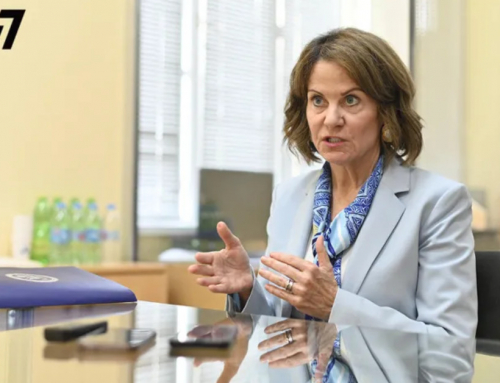

Teacher Lela Jincharadze (left), and Pariz Alakhverdiani. (DF Watch.)

Pariz, who lives with his parents in Duzagrama, says there are five pupils in his class who also want to continue studying at the university. The rest, he says, want to become a policeman, or teacher here in the village, or work at a farm.

There is only one girl in his class of 12. Many of the girls in school are engaged or already married. Pariz used to have four more girls as classmates, but they got married before they could finish school.

“I don’t think it is right, of course. I could understand marriage after school, but they have to study,” he adds.

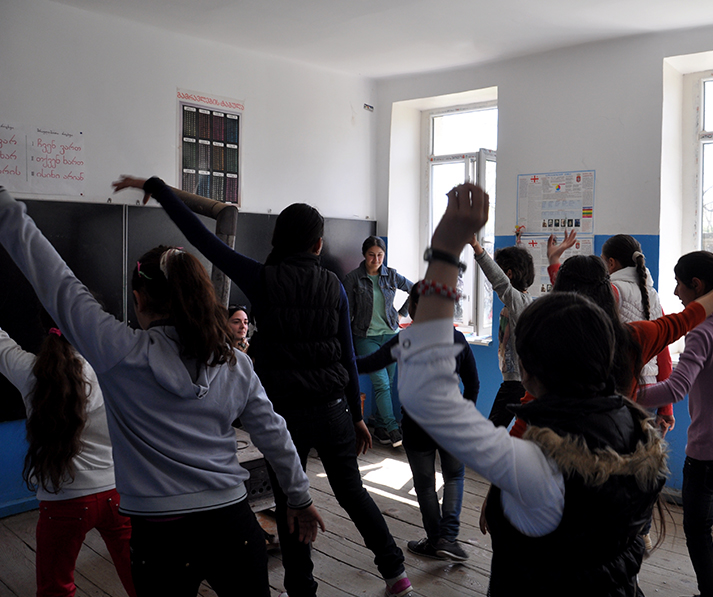

A dance class at Duzagrama school. (DF Watch.)

According to the teachers who teach Georgian language at the school, one of the biggest problems here is early marriage.

Lela Jincharadze, who has been teaching Georgian here for five years, says girls get married from eighth and ninth grade or get engaged and cannot finish school.

“This is not just a school problem, this is a social problem,” she says adding that so far government has no lever to somehow stop early marriages.

Muslim Abuzarov has been teaching at this school for 40 years. (DF Watch.)

“If you ask my pupils, girls and boys, all of them are against early marriage, but parents, religion and tradition have great influence.”

Lela thinks that the village situation may also be a controbuting factor. Marriages happen on the parents’ request without asking their children.

“We barely have girls from ninth grade here.”

Usually girls are forced to marry strangers. They happen to be people with business in Russia, or someone who arrived from Baku, people over 24 year takes 13-14 year old girls as wives.

“An uneducated mother raises an uneducated daughter and this keeps repeating, but the situation is improving from time to time and it is way better than it was, let’s say, in 2009.”

Muslim Abuzarov, a teacher in primary classes, confirms that many girls at the school get engaged.

“This is bad, this is very bad,” he says, proudly mentioning his own daughter as an example of the opposite. She graduated from medical university in Baku and has a successful career and only got married when she was 27.

In this school, there are two engaged girls in seventh grade. He thinks the reason also may be that the parents have low income and prefer that their children get married rather than sending them away for studies.

“Sometimes they do not have money to continue studying. They graduate school and stay here, getting married. It massively happens like that.”

Muslim remembered a girl, who was studying at 12th grade. Her father served in Afghanistan, got injured and died. Other relatives cannot provide money for her studying and now she got engaged. Her brother, who passed national exams and was accepted, couldn’t go to study because he couldn’t afford living in the city and stayed in the village.

Lela Jincharadze says they try to explain to children why it can be biologically bad to get married early.

“We try to be careful and not let them think we are pressuring them.”

Teachers say no-one comes here to help solve this or other problems. If anyone from non-governmental organizations or journalists come, everyone go to Iormughanlo and Lambalo, neighboring villages, where there are better roads. No-one bothers to go to Duzagrama.

According to Jincharadze, the three main problems in the village is early marriage, missing school due to nomadic family and less interest among parents for letting their children study.

Boys who do not study help their fathers in family works. They are used to work from early years, but this happens instead of education.

“Eastern traditions, religion, other things place women and children in a bad situation. Children are prepared for having to live like that,” she says.

“I’ve heard so many times from Georgian teachers in other villages that they’ve saved a girl from getting married and they managed to assure parents not to force their daughter to marry a cousin or a stranger.”

To solve this problem, Jincharadze thinks it is important that some other people, strangers, come here to control the situation and talk to people.

About three hundred children are attending this school, but many are missing classes. Many families are nomadic and travel a lot with their sheep. They take the children with them for three months who then have to miss school, but they have no choice but to move with their family.

“A person may be born and die here without leaving the village at least once, because they don’t need to,” she continues.

Over the last years people have gotten more interested in studying Georgian language in the village, especially youth. The government has a special program for non-Georgian speakers. They pass only one national exam in their own language, then study Georgian for one year and after that they can continue studying at the university.

The project made many young people make up their mind and think of studying in Tbilisi then going to Baku, as many used to continue studying in Azerbaijan. Georgian is being taught here from first grade.

There is also a Georgian language house in the center of the village and a language center where everyone, young and elderly people can study Georgian.

Khaial Gasanov is a teacher at the language center which was established in 2001. About 38 people are studying Georgian there now, half a dozen are adults. There are few women, and the girls are mostly from fourth or fifth grade.

The center teaches how to write, read and speak Georgian and usually a year is enough, Gasanov explains. There are three teachers at the center.

Muslim Abuzarov has been a teacher at this school for 40 years. He was born in Duzagrama, studied in Tbilisi and came back in 1973. Since then he has been here at the same school.

He remembers that about ten-fifteen years ago there were more than 700 pupils at the school and now about 300 are left.

People are leaving the village. Some left for Azerbaijan, Russia or Turkey and continue to leave, as there are no jobs here and the Azerbaijanian population don’t own lands to work on.

He says the school was recently refurbished and now there is a plan to change the floor.

One of the biggest problems the village has, he says, is transport, because people have to get a taxi to go to the closest town Sagarejo. The roads are bad and the local municipality doesn’t take care of them and there is only one medical center in the village, where there are a few doctors who only do diagnosis.

You have to go to the town for an operation or other medical issues. An ambulance needs 40 minutes to get to the village.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.