Giorgi Vashakmadze is Director of W-Stream Ltd, a company which promotes the Trans-Caspian and White Stream gas pipeline projects.

The EU is advocating stable and transparent regulatory rules for energy production and trade in countries that play an important role as energy suppliers, and especially in countries that are interested in closer ties with the EU.

Transparent and stable regulatory rules enhance a country’s attractiveness in the eyes of Western investors who conduct their business in accordance with best business practices and thus encourage investment inflows from the EU and the US, while on the other hand, diminishing interest of those who tend to benefit from non-transparent business environment. Greater transparency in how government deals with investors also make countries more resilient against intrusive external influences that can affect political decisions.

Georgia was invited to join the European Energy Community back in 2006. In the subsequent years multiple attempts were made by the EU and the US to encourage the Georgian leadership to apply for the membership to the European Energy Community, including the statement by the President of the European Commission, José Manuel Barroso in 2010 following his meeting with President Saakashvili. Had Georgia accepted the invitation, it would have enabled the country to considerably advance its energy and antimonopoly regulation reforms initiated and legislatively enacted earlier with the help of numerous grant programs funded by international donors. Georgia’s United National Movement (UNM) government chose not to get engaged and demonstrated utmost reticence on the subject, both vis-à-vis its western partners and its own society. Furthermore, they took the path of reversing the achievements of the previous reforms, further distancing the country from the requirements of the Energy Community.

Georgia was invited to join the European Energy Community back in 2006. In the subsequent years multiple attempts were made by the EU and the US to encourage the Georgian leadership to apply for the membership to the European Energy Community, including the statement by the President of the European Commission, José Manuel Barroso in 2010 following his meeting with President Saakashvili. Had Georgia accepted the invitation, it would have enabled the country to considerably advance its energy and antimonopoly regulation reforms initiated and legislatively enacted earlier with the help of numerous grant programs funded by international donors. Georgia’s United National Movement (UNM) government chose not to get engaged and demonstrated utmost reticence on the subject, both vis-à-vis its western partners and its own society. Furthermore, they took the path of reversing the achievements of the previous reforms, further distancing the country from the requirements of the Energy Community.

This situation changed after the new government assumed power following the 2012 elections: Georgia has officially applied for Energy Community membership. This is a remarkable change of Georgia’s posture for which the new government should be given due credit. But what has remained unchanged, is the lack of awareness of the society, even country’s NGO sector, about Georgia’s prospects of joining the European Energy Community and its potential benefits for Georgia’s future. The importance of stable and transparent regulatory rules has not been featured in media discussions. The role, nature or purposes of the Energy Community has never been explained to the society and even less is known about its role in securing country’s long-term political stability which in turn defines whether Georgia is perceived as a reliable ally to Europe’s energy supply diversification efforts, especially its strategic but extremely complex natural gas supply arrangements envisaged by EU’s Southern Gas Corridor plans.

Georgia successfully established itself as a reliable and instrumental transit partner while negotiating and implementing the East-West pipeline projects in the late 90s, early 2000s, but did nothing to keep or enhance this reputation after the Rose Revolution.

This is how Financial Times saw the situation just 3 weeks before the Russian military invasion of August 2008:

“The US and most European Union members support Georgia’s efforts to escape Russia’s influence and integrate with the west, including joining NATO. The west is also worried about the security of pipelines taking Caspian oil and gas across the Caucasus to Turkey. Meanwhile, a resurgent Russia sees the region, including the pipelines, as a key test of its capacity to reassert itself in the former Soviet Union.”

Another quote from the same article: “Abkhazia and South Ossetia are levers with which to put pressure on Tbilisi to slow its pro-west policies and drop its NATO bid. Dmitri Trenin, deputy director of the Carnegie Moscow Center, a think-tank, says: “Russia has no strong interest in Abkhazia itself. Russia is telling Georgia: ‘If you join NATO you will pay a very big price. You will never get back Abkhazia.”

Another quote from the same article: “Abkhazia and South Ossetia are levers with which to put pressure on Tbilisi to slow its pro-west policies and drop its NATO bid. Dmitri Trenin, deputy director of the Carnegie Moscow Center, a think-tank, says: “Russia has no strong interest in Abkhazia itself. Russia is telling Georgia: ‘If you join NATO you will pay a very big price. You will never get back Abkhazia.”

Those who have been participating in the East-West Energy Corridor development remember that similar messages were coming from Russian officials in relation to BTC in late 90s: If you allow building BTC – you will never get back Abkhazia.

Georgia was wise not to be swayed away from pursuing the development of these pipelines, nor its NATO aspirations.

Today, on the eve of signing major political and trade agreements with the EU, different government officials are frequently quoted saying that after the events of 2008, Russia has no more leverage over Georgia’s decision-making. What is apparently meant here is that no additional leverage remains for Russia in relation to Abkhazia and South Ossetia. But the question is whether the territorial integrity – a painful point mentioned by the Financial Times – is the only substantial weakness of Georgia that Russia has a possibility to exploit?

A weak and non-transparent energy sector opens another opportunity for meddling, though in more sophisticated and far less visible ways.

And in any case, a vulnerable and non-transparent energy sector means less reinvestments, less best practice, less competitive economy, less jobs.

When it comes to complex and geopolitically significant transit projects, it also means that the country is seen as a less reliable transit partner.

Timely adoption of the Energy Community standards could change the reality. Today, Georgia’s energy sector is much far away from the Energy Community standards of transparency and good governance then it was 9 years ago. This back-rolling was unjustifiable and unfortunate.

The United National Movement government has thrown away practically all legislative reforms that had been undertaken through and with the help of the US and EU funded institutional building programs. The practice was even worse. Meticulous ‘scientific’ justifications had been devised and offered to justify the need of vertically integrated players in Georgia, deriding the notion of strategic assets/infrastructure and abolishing regulatory instruments.

A one-time chance – the big privatization – conducted after the Rose Revolution, and highly praised in the West which was too busy to look into the details of this undertaking, have brought neither best business standards, nor sustainability to the sector.

A one-time chance – the big privatization – conducted after the Rose Revolution, and highly praised in the West which was too busy to look into the details of this undertaking, have brought neither best business standards, nor sustainability to the sector.

The main thing was ‘forgotten’ while praising Georgian ‘anti-corruption’ reforms and was overlooked by the public: non-transparent privatization of energy assets will allow for the stealing of a sizeable portion of the revenue for many years ahead.

Given the almost complete lack of information, it comes as no surprise that there was no public questioning of the reasons as to why, starting from 2006, Georgia was persistently ignoring EU calls to join the Energy Community.

Even when President Barroso publicly stated in 2010: “Concerning the diversification of energy sources and routes, the development of the Southern corridor is a key priority for the European Union. We attached great importance to the crucial transit role played by Georgia. And I encourage Georgia to formally apply for membership to the Energy Community. This would enable further deepening of our relations and reinforce Georgia’s attractiveness for energy investments”, there was complete silence from government officials as well as media and the expert community. This should have served as a wake-up call, but again, this fact was misinterpreted in the West: the West was convinced that Georgian reforms deserve just applause – not critical assessment.

In July 2010, the Eurasian Energy Analysis highlighted renewed attempts of the government to sell Georgian North-South gas pipeline that was just refurbished with grant money provided by US Millennium Challenge Corporation:

“Georgian Prime Minister Nika Gilauri promised that if Georgia sold shares of the pipeline, that the government would keep controlling interest. The opposition tried to hold the prime minister to his word by offering an amendment that would limit the sale of pipeline shares to 49 percent. Had the amendment passed, it would have been impossible for the government to sell control of the pipeline to any outside investors. Parliament rejected the amendment, leaving open the possibility that either GAZPROM or a GAZPROM affiliate could snap up the pipeline”.

Gazprom has been targeting Georgian North-South gas pipeline since 1995. Ownership of this pipeline and the right-of-way would potentially allow Russia to kill the projected large scale East-West gas transportation and flood EU countries with cheaper Iranian supplies via ‘Russian’ pipelines.

Such broader geopolitical considerations are important to keep in mind while negotiating some of the EC Treaty application for Georgia. This will require a thoughtful attitude from negotiating teams from both sides. As an example, Russia might demand to provide access for Gazprom to existing and future pipelines, basing its claim on certain provisions of the Treaty. Georgia, a bridge between the Caspian gas resources and the EU certainly has its geopolitical specificities that need to be taken into account.

Transit of a strategic commodity like gas is lucrative for countries and if the volumes are sizable, apart from cash dividends it is perceived to be bringing important geopolitical benefits.

The way the international diplomacy was using Turkmen gas transit as a high value bargaining chip and a possible ‘carrot’ to engage with Iran back in 2009, can serve as an illustration for the above: In response to the Turkmen President Gurbanguly Berdymukhammedov stating that ” …we are looking for conditions to diversify energy routes and the inclusion of new countries and regions into the geography of routes ”, Deputy Assistant Secretary of State George Krol has publicly suggested that the US remained open to the prospect of gas from Central Asia being exported to Europe via Iran.

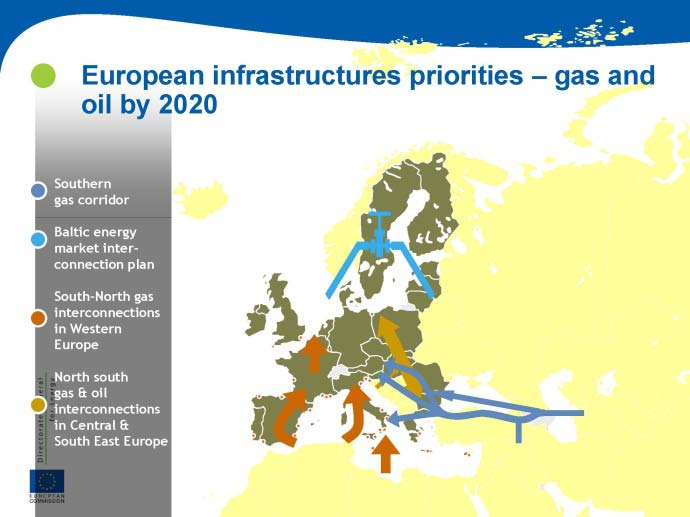

EU’s interest in new external pipeline supplies from new energy sources and through independent routes lead to the development of the Southern Gas Corridor plan and inclusion of this plan into the Connecting Europe Facility (CEF) scheme. The latter allows spending of EU taxpayers’ money for covering up to a half of the construction costs of SGC pipelines.The Southern Gas Corridor has been identified as one of four European infrastructure priorities in gas and oil by 2020.

A full-fledged Southern Gas Corridor is now perceived by all involved parties as a doable undertaking — an undertaking capable of achieving its declared strategic objectives of reliably supplying sizable quantities of gas to the European market.

For a long time Russia was trying to sow doubt about Turkmenistan’s reserves, and the costs and commercial feasibility of their development. Turkmenistan has overcome the difficulties and has proven not only the sustainability of its reserves, but also the possibility of extracting much more gas in commercially attractive manner.

Just in four years, a remarkably short time span for such developments, 22 wells have been drilled on Galkynysh. In September 2013 Turkmenistan hosted guests from various countries to celebrate the start of commercial production within phase one development of the field. The Government of Turkmenistan is building the so-called East-West pipeline that will have the capacity of 30 bcma by 2016 making it ready to supply gas into Trans-Caspian pipeline. Commercial development of the Galkynysh field has proven that Galkynysh is comparable to the super-gigantic South Pars field shared by Qatar. In addition, as President Berdymukhamedov has publicly stated, Turkmenistan will soon have 10 bcma production in the Caspian offshore.

For two decades the EU has been working on gaining access to the Caspian’s energy resources, particularly to Turkmen gas, but the recent developments with SD2, TANAP and TAP are certainly creating a momentum for the EU to push the Caspian agenda even stronger than before. These developments create favorable conditions for Georgia to join the team and become a helpful and reliable ally to the EU and Caspian suppliers in implementing the Trans-Caspian Pipeline. It is only through joint, concerted efforts that the success can be ensured. EU efforts are clearly aiming towards the implementation of the TCP, as a part of multi-project bundles within the SGC scheme before 2020. Georgia can help in midwifing these plans, or can remain a watcher hoping to harvest the fruits if others succeed in doing the job.

The changes over the past decade in global energy affairs have been unprecedented. The global energy map has been redrawn as a result of the unconventional oil and gas revolution in North America and the emergence of large energy consumers in Asia. EU countries are extensively subsidizing the renewables and emergence of North American cheap coal to the European markets has contributed towards further shrinkage of EU gas market. Now the prospects of Iran opening are perceived as more realistic in medium term. Georgia needs to see these and other developments as an encouragement to start playing an active role in Southern Gas Corridor developments. EU market will need the TCP, but this need will not be permanent – other developments will certainly make it less necessary if the current window of opportunity is lost. And it is vital that Georgia thoughtfully embraces opportunities of the Energy Community to free itself from the ties of non-transparent relations with its current energy players invisibly influencing its future.

Giorgi Vashakmadze is Director of W-Stream Ltd, a company which promotes the Trans-Caspian and White Stream gas pipeline projects. This article was first published February 20, 2014, in connection with a seminar in Tbilisi organized by Foundation World Experience for Georgia, devoted to a visit by Gunther Oettinger, EU Commissioner for Energy.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.