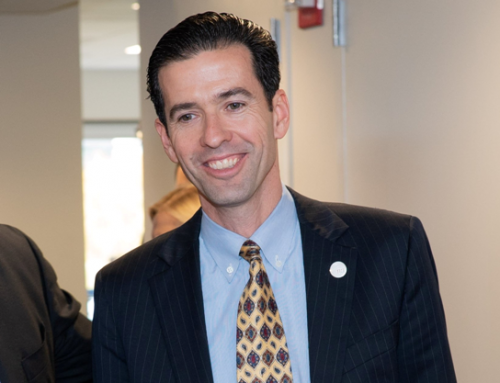

Paul Stronski is a senior fellow in Carnegie’s Russia and Eurasia Program, where his research focuses on the relationship between Russia and neighboring countries in Central Asia and the South Caucasus.

Voice of America’s Ani Chkhikvadze sat down with Paul Stronski, Carnegie Endowment fellow in Washington DC to discuss Georgia’s domestic and foreign affairs.

VOA: 100 years past since Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan declared independence from the Russian Empire. A century later, Russia in various degrees tries to keep influence over the three countries. Have Tbilisi, Baku and Yerevan been able to establish themselves as viable states and what are issues that persist after 100 years?

Paul Stronski: I think it depends on the country and it depends on what institutions you’re talking about. Of the three countries, I would say that Georgia is the one with the strongest institutions and it’s probably the one that has carved out as much independence as is possible when you are a small country next to a very large and aggressive neighbor. Georgia has had multiple governments, multiple elections, it has strong political institutions, much stronger than some of its neighbors. And yes, I do think this is very much a time to celebrate. I think you know a lot of the historic celebrations they look back at these early periods of independence with rose colored glasses, I mean they were all semi successful but they all had their own problems. And I think instead of just celebrating the past, the societies, really need to talk about the current problems of today and make sure that their institutions and their countries are accountable to them. As far as Armenia and Azerbaijan, I think Armenia is right now in the process of developing new institutions. Armenia has had a perennial problem of democracy of the street, and I think we’ve most recently seen that where the institutions aren’t very strong. It’s very one person, two people, centered rule that is very dependent on Russia. They seem to have tried to break out of that and only time will see how Armenia moves beyond that. And vis-a-vis Azerbaijan, it does have strong institutions and strong institutions of the Aliyev family. But beyond that it’s quite unclear what the other institutions of the state are. But all three they are you know vibrant societies they’re very engaged societies and you know they’re recognized internationally as independent states with specific borders. They’re in international institutions and we’ve come a long way in not just the 100 years but really in the past 25 years with all three countries where they actually have created independent states for themselves that are not subsidiary to Russia.

VOA: The questions that surround Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan’s ascending to power are if he can reduce corruption and improve socio-political situation in the country. What does Armenia’s so-called velvet revolution mean for internal and external developments?

Paul Stronski: Well, internally I think it’s got a huge importance. I mean the Armenian protests the protest movements that led to former prime minister Sargsyan’s resignation. They were very much about public anger over the status quo and the status quo where the average person was disenfranchised. So they wanted better accountability and greater transparency, greater anti-corruption efforts. Sargsyan government in its last two years had tried to sort of push through some of those efforts. But it was too little, too late. But the problem that Pashinyan now faces is that the expectations are really high. And he doesn’t have full control over parliament. You have the former ruling party which remains very cohesive body, still dominating parliament and Pashinyan also had to do a deal with one of the biggest oligarchs Gagik Tsarukyan. And when you rise to power through a political deal with an oligarchic party, it raises questions over how successful you automatically will be. I’m hopeful that they’ll be addressing these issues. The Armenian public seems to want them to address these issues but I think slogans that helped lead to the downfall of the previous government are easier than actually building concrete policies to fight corruption. We’ll see. Hopefully he’ll be successful. I think the Armenian people will give him some time but it won’t be eternal. And we’ll have to wait you know probably about a year, we’ll have a sense of where it goes.

VOA: In case of Armenia, Moscow’s reaction differed from what we have seen in case of Georgia and Ukraine. Russia has blamed the West for causing instability and instigating protest. It viewed Color Revolutions and later Maidan as a Western project rather than a genuine political uprising. What explains this difference in Moscow’s position, especially considering that Armenians refused to accept their leader, Sargsyan’s move- to following Putin’s steps and stay in power?

Paul Stronski: I think there’s a couple of things at play. One, I don’t think Russia was in love with Sargsyan. Sargsyan was the person who renegotiated a comprehensive engagement partnership with Europe. So he’s the person who was pivoting once again away from Russia. I think there was no love lost between the Kremlin and Sargsyan. The second, I actually do think that the Kremlin really miscalculated very badly during the Maidan and their actions of blaming the west and ultranationalists in Ukraine of seizing Crimea and of starting a war in eastern Ukraine. They built up off a lot to chew. And they’ve had repercussions internationally and domestically since then. Russia has learned that Ukrainian experiment very sadly isn’t going as well as the West and as well as the Maidan protesters would like. The Kremlin probably was thinking let’s just play a little bit more of a take a back seat, see how things develop and then figure out a way to work with whoever comes to power. It was a combination of two. One realizing that they overstepped in Ukraine to their detriment. And the second is that there was no love lost for the former prime minister/president.

VOA: Georgia has been cautious vis-a-vis Russia. The Georgian Dream government in Tbilisi on many occasions has emphasized that they are dealing with Moscow pragmatically. However, we see that Russia continues aggressive policy towards Georgia, be it either further integration of the occupied regions or cases of Georgian citizens getting kidnapped and murdered, borderization at the occupation line, and so forth. In this light, can we say that despite Georgia’s approach, Moscow’s actions will not change?

Paul Stronski: Georgia needs to remember that Russia is a very aggressive country, it’s right on your borders and it has no qualms about doing what it does. You can see that in Ukraine, you saw that in 2008. Georgia has very limited options and maybe the Saakashvili provocation probably wasn’t the right option with a very aggressive Russia, and perhaps the Georgian Dream is being a bit too soft on it [Moscow]. But I think some of what they are trying to do in a long-term is positive: enhance trade, enhance people to people contact, try to get everybody in South Ossetia and Abkhazia to understand the benefits of Georgia’s pro-Western orientation. I think that is all positive and that in the long term will probably help the people of South Ossetia and Abkhazia realize that they have a very difficult situation that they’re in. But at the same time they are very much also controlled by a very aggressive Russia in what they can do. The options that Georgia has are not great. And I think continuing some of what they’ve been doing, of trying to work hard on making Georgia a successful, multiparty government that works on improving the lives, the standard of living, the opportunities for Georgians. I think probably that is what the government should be focusing on. There have been some signs of concern in Georgia recently. And I think the government really needs to work to make sure that there is a strong opposition, that is an empowered opposition. And also try to figure out how to jumpstart the economy and to have a more robust economy across the board. There are tremendous opportunities from the Association Agreement with Europe. But those opportunities are not broadly distributed to the Georgian people. If you’re wealthy you can go to Europe a lot easier. But the majority of people can’t do that. And so how do you make these new trade and travel agreements work for the Georgian people. I think there needs to be a little bit more investment in trying to make that happen.

VOA: In two separate cases of Azerbaijan and Turkey we saw authoritarian inclinations and political vendetta transcend their borders. I am referring to the case of Azerbaijan journalist, Afghan Mukhtarli who was abducted in Georgia, and case of Turkish teacher, Mustafa Emre Chabuk that Turkey has seeking for terrorism charges and is requesting his extradition. In both cases, Tbilisi had to balance strategic partnership with human rights protection. What’s the best way out of this impasse and what can Tbilisi do?

Paul Stronski: Well, Georgia needs to be very careful about what it does in the situation, there’s a lot of questions particularly about the Azerbaijani journalist and what role or what amount of knowledge the Georgian government, Georgian security services, had. And those are important questions to ask. You know Georgia is a democracy, Georgia is a very pro-Western country and some of the questions that have to be asked when these types of events happen are concerning. And concerning about Georgia’s commitment to this Western trajectory. I think the extra-judicial reach of many authoritarian countries is very troubling. Azerbaijan and Turkey are just several of them. But you go to Central Asia where governments are trying to get their citizens get their opponents from outside their borders. Georgia is a relatively safe place for exiles from the region and is going to be facing this problem more and more and Georgia needs to do everything it can to welcome these people and provide them with a safe place to continue doing their work. If you know they are wanted on extremism charges, you look at what those charges are but be aware of where the evidence is coming from. And beware of the political methods that many authoritarian governments use to try to silence their opponents.

VOA: 10 years passed since the NATO Bucharest Summit. Georgia is often praised for its political and military reforms, and contribution to the NATO missions. However, the countries in the West remain reluctant to grant Georgia the Membership Action Plan. Are we going to see enlargement discussion coming back and what should Georgia’s strategy be to get more from the NATO?

Paul Stronski: There are certainly people who are going to want to enhance and enlarge NATO. But I’ll just be plainly blunt here. The Trump administration is no fan of NATO itself and the Trump administration in the United States is questioning NATO’s purpose and so far, isn’t pulling out of the alliance and I don’t think that happens. But we have an American administration that is not focused in on the alliance and would much rather do bilateral defense relationships. I think this is an opportunity for Georgia to really sort of you know move away from sort of the big NATO discussion and move towards enhancing its bilateral defense cooperation even more than it is with the United States. That is the type of relationship that the Trump administration seems to be pushing. There have been some recent articles in the U.S. press that some of the most robust military to military cooperation between the United States and European partners is actually with non-NATO states, Finland and Sweden, and those are models for Georgia to look at, how you can you can sort of try to build a closer cooperation in the defense sector.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.